What we call campaigns in 2023 are anything but. The term is an anachronism, carried over from the war gaming roots of roleplaying games (RPGs) when characters were soldiers with personalities. Campaigns are long-term military plans of many missions, which if a roleplaying game is a crusade against a great evil, makes sense. However, that is not how Gary Gygax described it nor how it became defined later.

Primary sources

It’s hard to find any concrete definition from Dungeons and Dragons’ creators. Game books from the late 1970s seldom bother with clear terminology; with a small early readership, authors assuming their auiences were familiar with the hobby. However, Gygax provided his vision for a superior campaign speaking directly to Dungeon Masters:

It’s hard to find any concrete definition from Dungeons and Dragons’ creators. Game books from the late 1970s seldom bother with clear terminology; with a small early readership, authors assuming their auiences were familiar with the hobby. However, Gygax provided his vision for a superior campaign speaking directly to Dungeon Masters:

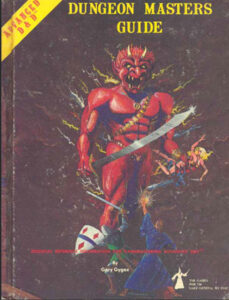

“a superior campaign … offers the most interesting play possibilities to the greatest number of participants for the longest period of time possible. You, as referee, will have to devote countless hours of real effort in order to produce just a fledgling campaign, viz. a background for the whole, some small village or town, and a reasoned series of dungeon levels — the lot of which must be suitable for elaboration and expansion on a periodic basis.”

—Preface, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide (1979)

From this point, it’s clear the campaign was supposed to be more than just a military plan. “A background for the whole” suggests a lot, varying from local history to the universe, depending on many factors. But far more telling is “the most interesting play possibilities to the greatest number of participants for the longest period of time possible,” which is an unbounded goal, truly ambitious, and suggestive of the multitude of tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) we in 2023 can enjoy.

But my point remains that the term campaign doesn’t fit the implied definition here. A fledgling campaign was history, geography, demographics, dramatis personae, mystic secrets, town and dungeon, etc. Further, “the most interesting game play possibilities” must go beyond the military aspects of a crusade, as romances, political intrigues, follies, commercial ventures, great works of art, and basically anything else you can imagine should be possible in the superior campaign. The players are given rules and themes, but the goal of military progress is simply too small.

Campaigns through the Ages

There are games that have resolved that combat is the most dramatic and interesting play possible, so do not attempt to deviate from the standard definition of the campaign. If you’ve played Warhammer 40000, either the strategy game with miniatures or one of the roleplaying games where the players play various military actors in that universe, you can see how the game and setting embrace the military campaign concept by design. In these cases, I would agree that campaign is an apt term for a series of skirmishes, operations, logistics, and so on, the characters play through just as a military planner would design it.

D&D, however, provides the definition later that is still broader than the conventional one, but comparatively tame and well bounded compared to Gygax’s:

“A campaign is a series of DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game adventures involving the same group of characters, and taking place in the same fantasy setting.”

— Running a Campaign, The Classic Dungeons & Dragons Game (1994)

This definition seems designed to make products, very close to many commercial games, film, television, online video, and book franchises we recognize today. It conforms to a market definition of what a campaign should be – note the absence of participants, time, and possibilities. At this point in TSR’s history, this matched their goals, quite different from the material that preceded it. But again, not a military plan, but a corporate one. Such an RPG campaign is more like a political or marketing campaign, convincing everyone to play this game or that because it’s the most fun or even “the world’s greatest roleplaying game.” Fortunately, this supports further abandoning the term unless we as game designers are more interested in the marketing aspects of the game than the game experience. It’s a viable choice, but not one we prefer.

If not Campaign, then What?

When we think of possible terms to subvert the common campaign, we are reminded of a particularly popular “replay” serialization (think live stream play, but low tech) from the late 1980s called Record of Lodoss War, which is an approximate translation of its Japanese name. We wonder what the actual word was in the original title indicating a record of something, because the term probably has no exact English equivalent, but record does not sound very fantastical. The choice of names matters to signal the style and mood of a game, which is why we think Campaign does not adequately describe the long-play possibilities of any good fantasy setting.

When we think of possible terms to subvert the common campaign, we are reminded of a particularly popular “replay” serialization (think live stream play, but low tech) from the late 1980s called Record of Lodoss War, which is an approximate translation of its Japanese name. We wonder what the actual word was in the original title indicating a record of something, because the term probably has no exact English equivalent, but record does not sound very fantastical. The choice of names matters to signal the style and mood of a game, which is why we think Campaign does not adequately describe the long-play possibilities of any good fantasy setting.

When we ran World of Darkness games, extended play was called a Chronicle, which is accurate for a series of stories that may span several human generations. It suggests the sort of big, old books sea captains and explorers would compile of their journeys. This seems much more from the player’s perspective and not the referee’s, who must know the stakes and outcomes of a campaign, which the players do not at the outset. They may pass by or overlook many things included in the campaign materials or even take the story in an unexpected direction. This suggests that any term describing the past shall not suffice either and history sounds dull anyway. Chronicle is at least a contender.

A season sounds a lot like sports or television programs. Series is accurate, but lacks any flavor, almost a technical term. Myths are of varying length, but a long myth like the stories of Hercules, Inanna, or Moses are long enough to span a complete set of modules. Trilogy, Song, Saga, Cycle, Lay, and Epic all come very close, as they describe a poetic record of an entire hero’s journey like Theseus or Rama (among many others) which may or may not include a war. A Song of Fire and Ice is the overarching title of George R. R. Martin’s epic story for this reason.

But the truly fantastical but credibly real stories are none of these, they are legends. They can be named for many things, including the antagonists. It diminishes with fictionalization, as the real actions of the characters have power because of its alleged authenticity. A legend can be romantic or horrific, it can be tragic or comedic, it has every potential but the involvement of players, actors to perform the great deeds and desperate gambles. Our games will be legendary.